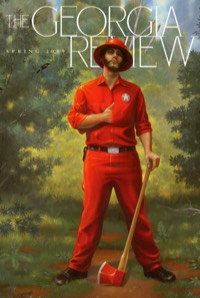

The Georgia Review, Spring 2009

THE WORLD CUT OUT WITH CROOKED SCISSORS: SELECTED PROSE POEMS. By Carsten René Nielsen. Translated by David Keplinger. New Issues Poetry and Prose, 2007. 103 pp.

Reviewed by Nicky Beer

It’s impossible not to read the opening poem of Danish poet Carsten René Nielsen’s first English-language translated collection, The World Cut Out with Crooked Scissors, as an ars poetica. In “Spider”, pandemonium erupts in a schoolroom when “the fat boy of the class” unveils his all-spider revue of Macbeth: the audience of students and teacher, in their hysteria, cannot appreciate the macabre marvel to which they are witness, nor that “he controls with fabulous precision, a cool passion, and he does all the lines himself in different voices.” The image of the diminutive puppet theater and the boxy form of the prose poem chime especially clearly here; subsequently, on page after page of Nielsen’s book, a curtain rises on abbreviated scenes and tableaus that are by turns absurd, witty, disturbing, and delightful.

[...]

Nielsen has a marvelous facility for reinventing the prose poem form–within the book’s tesserae of verbal boxes we find apocrypha of natural history, sadistic fables, journal-like fragments, ekphrasis, and folk remedies. Even more remarkable is the fact that almost half of them are written in the guise of “animal” poems–including, but not limited to, the first book represented in the selection, Forty-one Animals (2005). Certainly much of Nielsen’s work is suggestive of the anatomies of objects, elements, and animals found in the prose poetry and mini-essays of Francis Ponge. Ponge’s work is deeply engaged with reality and the Ding an sich, and Nielsen brings an equally attentive fidelity to the contours of our imaginative worlds–describing the dormouse that “nestles down to sleep inside the groove between one’s chin and lower lip” and a cow “so thin, the farmer has been forced to fasten its skin to its body with pins.” The poet takes it upon himself to translate those wordless montages and scenarios of the unconscious into concrete form for his readers, and the book serves as a compendium not unlike the locale of his poem “Sheep”: a “museum that exhibits animals only as we see them in dreams.”

Dreams, dreaming, and sleep are persistent themes throughout this work–even the book’s pervasive sense of eros has the languid, slightly menacing sexiness of an erotic dream. In “Sleep”, “if the sleep is deep enough, the soul sneaks into the bedroom and lies down a few hours beside your body. Like a betrayed woman who cautiously puts her arms around her sleeping lover.” These poems inhabit that specific genre of nocturnal improvisation in which, despite all evidence to the contrary, the dreamer is utterly convinced that she is awake. But these poems do much more than blur the line between illusion and reality: they evoke that vibrant contradiction of dreaming in which the real and unreal exist in perfect simultaneity, so that “you have keyholes instead of nipples” and “when you hang your clothes out to dry, suddenly you know the exact number of languages spoken by the clouds.”

[...]

The paradox for the translator is that the more skilled he is, the more invisible he will be–and yet works like The World Cut Out with Crooked Scissors prove that his centrality as a literary explorer/adventurer/anthropologist/advocate is invaluable. Without him, nonnative readers would likely be barred access to the strange-yet-strangely-familiar byways in Nielsen’s poetry, where we can observe “tiny, tiny birds [that] fly out of the mouths of the sun-bathing girls,” “birds [that] seem to know that they are being watched and do their best to fly carelessly, elegantly. As if the world were just a stage set for their sake alone.”

From the opening scene of Nielsen’s anarchic, aracnid Shakespeare performance onward, he renders a bestiary that is, ultimately, a habitation in which the unconscious and self-conscious merge into one marvelous hybrid. In the playful, eloquent image of the bird flying from a human mouth, we can also find a useful metaphor for the pleasure of reading good poetry in translation: the song and the source may be incongruous, but what emerges is undeniably and transcendently song.

THE WORLD CUT OUT WITH CROOKED SCISSORS: SELECTED PROSE POEMS. By Carsten René Nielsen. Translated by David Keplinger. New Issues Poetry and Prose, 2007. 103 pp.

Reviewed by Nicky Beer

It’s impossible not to read the opening poem of Danish poet Carsten René Nielsen’s first English-language translated collection, The World Cut Out with Crooked Scissors, as an ars poetica. In “Spider”, pandemonium erupts in a schoolroom when “the fat boy of the class” unveils his all-spider revue of Macbeth: the audience of students and teacher, in their hysteria, cannot appreciate the macabre marvel to which they are witness, nor that “he controls with fabulous precision, a cool passion, and he does all the lines himself in different voices.” The image of the diminutive puppet theater and the boxy form of the prose poem chime especially clearly here; subsequently, on page after page of Nielsen’s book, a curtain rises on abbreviated scenes and tableaus that are by turns absurd, witty, disturbing, and delightful.

[...]

Nielsen has a marvelous facility for reinventing the prose poem form–within the book’s tesserae of verbal boxes we find apocrypha of natural history, sadistic fables, journal-like fragments, ekphrasis, and folk remedies. Even more remarkable is the fact that almost half of them are written in the guise of “animal” poems–including, but not limited to, the first book represented in the selection, Forty-one Animals (2005). Certainly much of Nielsen’s work is suggestive of the anatomies of objects, elements, and animals found in the prose poetry and mini-essays of Francis Ponge. Ponge’s work is deeply engaged with reality and the Ding an sich, and Nielsen brings an equally attentive fidelity to the contours of our imaginative worlds–describing the dormouse that “nestles down to sleep inside the groove between one’s chin and lower lip” and a cow “so thin, the farmer has been forced to fasten its skin to its body with pins.” The poet takes it upon himself to translate those wordless montages and scenarios of the unconscious into concrete form for his readers, and the book serves as a compendium not unlike the locale of his poem “Sheep”: a “museum that exhibits animals only as we see them in dreams.”

Dreams, dreaming, and sleep are persistent themes throughout this work–even the book’s pervasive sense of eros has the languid, slightly menacing sexiness of an erotic dream. In “Sleep”, “if the sleep is deep enough, the soul sneaks into the bedroom and lies down a few hours beside your body. Like a betrayed woman who cautiously puts her arms around her sleeping lover.” These poems inhabit that specific genre of nocturnal improvisation in which, despite all evidence to the contrary, the dreamer is utterly convinced that she is awake. But these poems do much more than blur the line between illusion and reality: they evoke that vibrant contradiction of dreaming in which the real and unreal exist in perfect simultaneity, so that “you have keyholes instead of nipples” and “when you hang your clothes out to dry, suddenly you know the exact number of languages spoken by the clouds.”

[...]

The paradox for the translator is that the more skilled he is, the more invisible he will be–and yet works like The World Cut Out with Crooked Scissors prove that his centrality as a literary explorer/adventurer/anthropologist/advocate is invaluable. Without him, nonnative readers would likely be barred access to the strange-yet-strangely-familiar byways in Nielsen’s poetry, where we can observe “tiny, tiny birds [that] fly out of the mouths of the sun-bathing girls,” “birds [that] seem to know that they are being watched and do their best to fly carelessly, elegantly. As if the world were just a stage set for their sake alone.”

From the opening scene of Nielsen’s anarchic, aracnid Shakespeare performance onward, he renders a bestiary that is, ultimately, a habitation in which the unconscious and self-conscious merge into one marvelous hybrid. In the playful, eloquent image of the bird flying from a human mouth, we can also find a useful metaphor for the pleasure of reading good poetry in translation: the song and the source may be incongruous, but what emerges is undeniably and transcendently song.

Carsten René Nielsen

Carsten René Nielsen